|

Investigations sposored by a 2021 NCPTT Grant

|

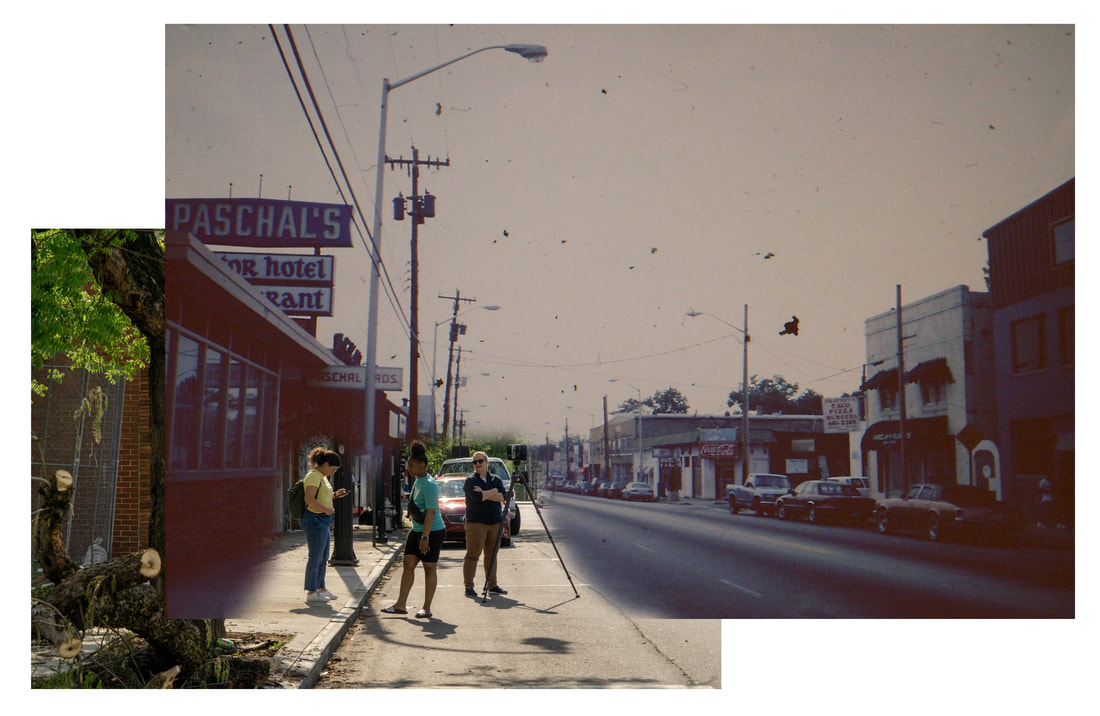

In 1947, brothers Robert and James Paschal opened a small sandwich shop. A decade later, the restaurant moved to a new location across the street at 837 Hunter Street NW to accommodate more customers. First cited in the 1950 edition of The Green Book, and the Paschal Brothers’ Restaurant would be a regular feature within the guide until the final edition of the Travelers’ Green Book: 1966-67 International Edition for Vacation without Aggravation. By this point, the enterprise had blossomed to include an entire entertainment complex, with a jazz club and motor inn. Renowned for its food and hospitality, it was a safe haven for Black travelers, and where those arrested at peaceful sit-ins or marches could receive a free, hot meal after their release, no matter the time of day. As a secure place for civil rights leaders to gather, Paschal’s become known as “Black City Hall.”

Here, Black and white patrons gathered in the same dining room, a radical configuration for the typical landscape of the segregated south. As acknowledged by student propositions, one of the most transformative aspects of the site was also the most quotidian: the table. Evolving from a lunch counter to a large-scale restaurant, Paschal’s continued to foster community through repast. Sustenance could be found in celebration and reflection: John Lewis noted he last saw Martin Luther King, Jr. alive at the restaurant. In 1976, Paschal’s iconic address was renamed to 830 M.L.K, Jr. Drive SW, and this was fortuitous in more ways than one. It acknowledged King’s roots in the city and his important legacy, and the street’s rechristening removed reference to an injurious facet of Atlanta’s antebellum era: Hunter was one of Atlanta’s largest slaveholders. Once the cornerstone of westside Atlanta that served generations of progressive advocates and policymakers, the site of Paschal’s Motor Hotel and Restaurant is currently in a precarious state. The restaurant’s features are barely recognizable along the sidewalk, only the skeletal frame of the roadside sign remains, and debris litters the shuttered balconies of the International Style hotel. Despite its current state, Paschal’s is a symbol of resilience. In 1996, Clark Atlanta University purchased the famous site, operating the restaurant and a dormitory in the former inn until 2003. Barely escaping the wrecking ball and ongoing litigation, the site continues to move towards demolition by neglect. As a business, Paschal’s is still thriving within a larger location in Castleberry Hill and enterprises at Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson Airport. This, however, highlights the disconnect between preservation and entrepreneurialism, history and progress. |

A Google Earth aerial, overlaid with historic imagery.

A Google Earth aerial, overlaid with historic imagery.

Historal Context

|

In the 1960's the West Hunter Street (now Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive) corridor in Atlanta, Georgia was crucial to the American Civil Rights Movement and a center for Black Atlantans, hosting meeting places for movement leaders, headquarters for civil rights organizations, churches, HBCU's, and businesses. Today, however, many of the businesses, homes, churches, and other buildings that once anchored this area have been lost – be it to demolition, fire, or abandonment. Centered around one such abandoned building that was crucial to the Civil Rights Movement – Paschal's Restaurant – this project seeks to rebuild in 3D the West Hunter Street corridor across its early development, its most prominent time during the Civil Rights Movement, and its present situation. The creation of this series of models explores the possibilities of layering content in 3D to create holistic, accurate reconstructions which would otherwise not be possible. Combined, the 3D models allow viewers to see three key eras from the history of the West Hunter Street corridor. Included within the models is the ability to visualize key moments from the history of the neighborhood through the combination of the 3D model with historical photos.

To understand Paschal’s, it was key to place it in the context of the West Hunter Street/Martin Luther King Jr. Drive corridor that surrounded it. A 4500-foot-long section of the corridor was chosen to be modeled, stretching from Northside Drive (previously Davis Street) to Joseph E. Lowery Boulevard (previously Ashby Street), along with approximately 200 feet to either side. Three moments were chosen to understand the history of the neighborhood – the year 1911, when the neighborhood was developing and seeing its first commercial ventures; the year 1968, the year of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination and after the neighborhood flourished during the Civil Rights Movement; and 2022/2023, showing the neighborhood and Paschal’s as they presently exist. Prior to the commencement of the project, we were denied access to the interior of Paschal’s by Clark Atlanta University due to structural and liability concerns about the building, necessitating a reconstruction of the interior of Paschal’s without access. |

Historic Visualizations

content with Thomas Bordeaux

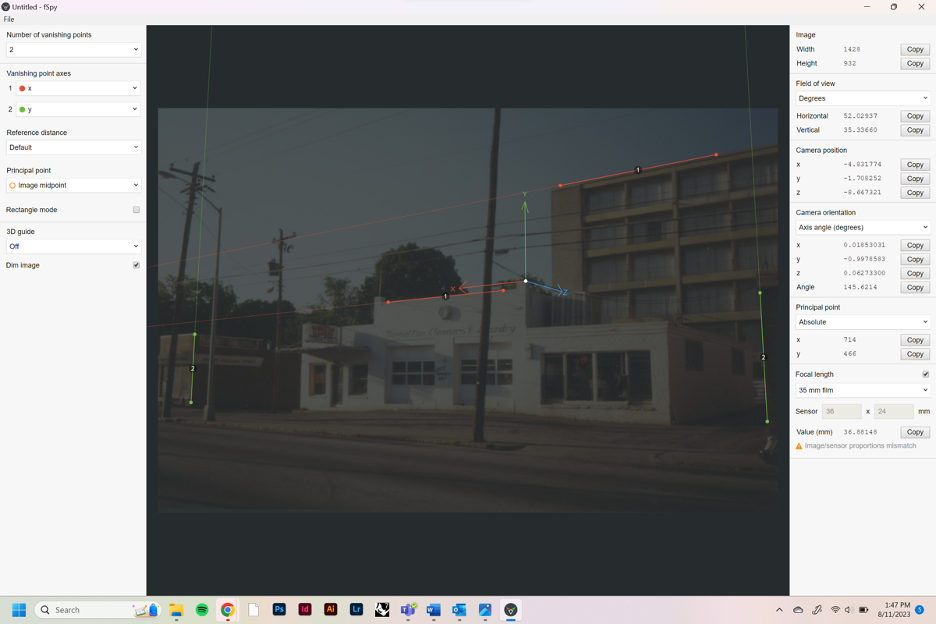

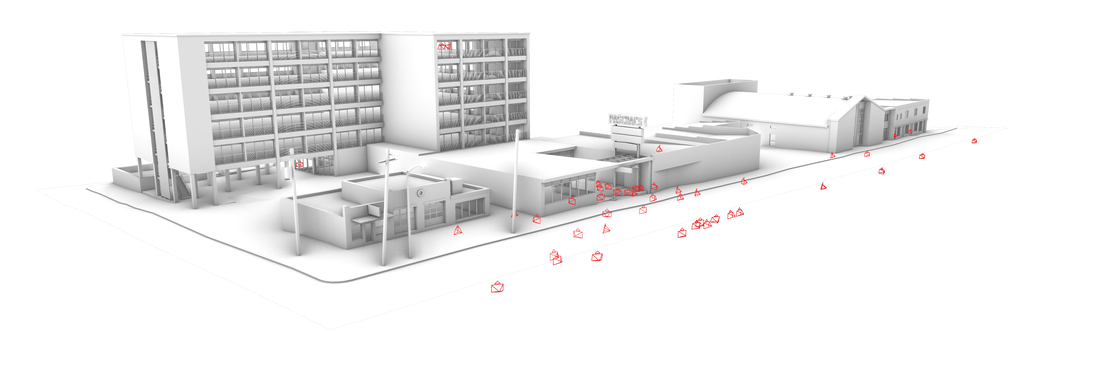

Due to a lack of photographs surrounding the 1911 3D reconstruction, for buildings that are no longer extant, Sanborn Maps were traced in 3D and extruded according to heights or floor levels shown on the maps. Extant buildings within the study area were 3D scanned either via LiDAR or photogrammetry to represent them in 3D space accurately. For some buildings, to represent them accurately in 1968, further modeling was required. The following image below shows the in-progress 3D modeling of Paschal’s based on LiDAR scans of the building using standard 3D modeling techniques.

Throughout the early 20th century, the neighborhood continued to develop. In the early 1930s Robert Paschal came to call it home, waiting tables at a cafeteria and serving at a soda fountain. Despite limited job prospects due to segregation, he rose to prominence in the black social scene of the city, eventually earning the moniker “Mayor Paschal.”

His younger brother, James Paschal had stayed behind in their hometown of Thomson, Ga, a rural community near Augusta, operating a paper route, a vegetable market, several shoeshine stands, mail-order cosmetics sales, and a small convenience store. After serving in World War Two and a brief stint as a Pullman porter, James reunited with his brother in Atlanta, pooling their savings to open a sandwich shop named Paschal’s in 1947. Using their mother’s fried chicken recipe, Robert Paschal served as the restaurant’s cook while James Paschal handled the administrative side of the business. The restaurant quickly became popular with students at the nearby colleges. In addition, the restaurant gained popularity with another patronage – Black businessmen and politicians who were barred from downtown restaurants by segregation.

However, unlike these downtown restaurants, Paschal’s did not practice segregation in open defiance of laws forbidding integrated restaurants. Instead, Paschal’s acted as a common ground where Black and white Atlantans could meet, talk, or debate the day's news. In 1959, with its growing success, the restaurant moved across the street and the following year added the La Carousel Lounge. In 1967 they would add a 120-bed hotel attached to the restaurant.

While Paschal’s was gaining more prominence so was the neighborhood and its role in the civil rights movement. West Hunter Street and the surrounding blocks were home to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, Sr.’s church, the headquarters of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, as well as numerous black businesses and others involved in the civil rights movement.

His younger brother, James Paschal had stayed behind in their hometown of Thomson, Ga, a rural community near Augusta, operating a paper route, a vegetable market, several shoeshine stands, mail-order cosmetics sales, and a small convenience store. After serving in World War Two and a brief stint as a Pullman porter, James reunited with his brother in Atlanta, pooling their savings to open a sandwich shop named Paschal’s in 1947. Using their mother’s fried chicken recipe, Robert Paschal served as the restaurant’s cook while James Paschal handled the administrative side of the business. The restaurant quickly became popular with students at the nearby colleges. In addition, the restaurant gained popularity with another patronage – Black businessmen and politicians who were barred from downtown restaurants by segregation.

However, unlike these downtown restaurants, Paschal’s did not practice segregation in open defiance of laws forbidding integrated restaurants. Instead, Paschal’s acted as a common ground where Black and white Atlantans could meet, talk, or debate the day's news. In 1959, with its growing success, the restaurant moved across the street and the following year added the La Carousel Lounge. In 1967 they would add a 120-bed hotel attached to the restaurant.

While Paschal’s was gaining more prominence so was the neighborhood and its role in the civil rights movement. West Hunter Street and the surrounding blocks were home to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, Sr.’s church, the headquarters of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, as well as numerous black businesses and others involved in the civil rights movement.

|

|

1968, video A

Atlanta’s civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, Julian Bond, and John Lewis, most of whom were already Paschal’s regulars, planned many well-known campaigns in hotel rooms and booths at Paschal’s. Among the most notable campaigns planned at Paschal’s are the Selma to Montgomery Marches, the March on Washington, Mississippi Freedom Summer, and the Poor People’s Campaign. But Paschal’s wasn’t just a meeting place for the high-level planning of the civil rights movement – it also served as a shelter for protesters, as a place to enjoy a free meal after they were released from jail. |

|

|

1968, video B

Just three weeks after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. held meetings at Paschal’s as part of the planning for the Poor People’s Campaign he was assassinated in Memphis, TN. The assassination rocked Hunter Street and the nation. Five days after his assassination, on April 9th, 1968, Martin Luther King would pass by Paschal’s for a final time as part of a four-mile-long funeral procession from Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Dr. King was pastor to Morehouse College, where a public ceremony was held. |

1968, video C

Following its prominence in the 1960s and in the wake of desegregation, Paschal’s carried on with a large integrated customer base, but one that was still smaller than before. Many gatherings and events migrated to the large downtown restaurants and hotels the Paschal brothers had fought so hard to desegregate. However, the restaurant persisted, continuing in its role as a political kingmaker. Black leaders continued to use the facilities as a staging ground for social justice activities, and local and national politicians recognized it as a place to speak to their constituents.

Throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s, Black and white civic and religious groups continued to meet at Paschal’s, as did many national politicians. Jesse Jackson launched his 1984 and 1988 Presidential Campaigns at Paschal’s, and Jimmy Carter, Hubert Humphrey, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton all visited Paschal’s during their presidential campaigns. During this time the Paschal Brothers expanded to an additional location in the Hartsfield Jackson International Airport. However, the health of Robert Paschal was declining and in response the Paschal brothers made the decision to close the restaurant. In 1996 the restaurant, jazz club, and hotel were sold to Clark Atlanta University for three million dollars to be used as a restaurant, conference center, and student dormitories to be named The Paschal Center. Even though the old staff were being kept and the building would remain, it was recognized at the time that the feeling of the restaurant would be permanently altered.

Robert Paschal died the following year at eighty-eight. After his brother’s death James Paschal set into motion plans to reopen the restaurant and did so in 2002 a few miles from the original location. At this same time Clark Atlanta University was having problems with The Paschal’s Center, posting a half-million dollars a year in losses. To halt this loss, they closed the center in 2003 and announced plans to demolish the structure, even receiving a permit to do so. However, following national outcry and an eleventh-hour preservation effort, the entire complex was protected from demolition.

Following its prominence in the 1960s and in the wake of desegregation, Paschal’s carried on with a large integrated customer base, but one that was still smaller than before. Many gatherings and events migrated to the large downtown restaurants and hotels the Paschal brothers had fought so hard to desegregate. However, the restaurant persisted, continuing in its role as a political kingmaker. Black leaders continued to use the facilities as a staging ground for social justice activities, and local and national politicians recognized it as a place to speak to their constituents.

Throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s, Black and white civic and religious groups continued to meet at Paschal’s, as did many national politicians. Jesse Jackson launched his 1984 and 1988 Presidential Campaigns at Paschal’s, and Jimmy Carter, Hubert Humphrey, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton all visited Paschal’s during their presidential campaigns. During this time the Paschal Brothers expanded to an additional location in the Hartsfield Jackson International Airport. However, the health of Robert Paschal was declining and in response the Paschal brothers made the decision to close the restaurant. In 1996 the restaurant, jazz club, and hotel were sold to Clark Atlanta University for three million dollars to be used as a restaurant, conference center, and student dormitories to be named The Paschal Center. Even though the old staff were being kept and the building would remain, it was recognized at the time that the feeling of the restaurant would be permanently altered.

Robert Paschal died the following year at eighty-eight. After his brother’s death James Paschal set into motion plans to reopen the restaurant and did so in 2002 a few miles from the original location. At this same time Clark Atlanta University was having problems with The Paschal’s Center, posting a half-million dollars a year in losses. To halt this loss, they closed the center in 2003 and announced plans to demolish the structure, even receiving a permit to do so. However, following national outcry and an eleventh-hour preservation effort, the entire complex was protected from demolition.

|

|

2022

While the building remains, the building has largely been neglected since 2003. At present, nearly all the windows have been broken or boarded up and many of the interior walls and ceilings have collapsed leaving debris piled inside. Water has made its way into the building causing farther severe damage. Perhaps at this point, more than any other, the future of this structure is uncertain. The neighborhood, too, faces an uncertain future. Much of it lies abandoned, and a series of fires have damaged historic buildings at Morris Brown. Similarly, the Walmart was damaged by fire in 2022 and has been closed since, leaving the surrounding community in a food desert. However, there are hopeful signs both for the neighborhood and Paschal’s. A series of grants from the National Park Service has restored the West Hunter Street Baptist Church and provided a new roof for Fountain Hall. Additionally, the Atlanta University Center Consortium, comprised of Clark Atlanta University, Morehouse College, the Morehouse School of Medicine, and Spelman College has produced a master plan for the consortium that includes, among numerous other points, the restoration of Paschal’s. However, without support the Paschal’s complex will be lost to history. |

While the exterior of Paschal’s and other buildings along the corridor in the 1968 3D reconstruction enjoyed rich photographic coverage, the interior of Paschal’s, which we were denied access to, did not enjoy the same coverage, despite having many photographs of it. These difficulties were caused by disjointedness among different parts of the building – not all parts of the interior enjoyed the same coverage and where photographic continuity was broken – such as on stairs, around corners, and through doors – so too was the continuity of the 3D reconstruction. Additionally, many of the rooms in Paschal’s are windowless or subterranean making solving this puzzle of interior photograph locations even more difficult. These discontinuities would be key to observe early on in other similar reconstructions in hopes of avoiding them.

|

The resulting work product represents an initial public facing history of the West Hunter Street/Martin Luther King Jr. Drive corridor, combining these 3D models with new oral histories and previous accounts would create a stronger dialogue between the public and the created 3D representations of the West Hunter Street/Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive corridor. Further, as many people who experienced Paschal’s between 1947 and 2003 are still alive, a concept known as “situated testimony," pioneered by the UK-based investigative group Forensic Architecture could explore reconstructing the as-of-yet unreconstructed portions of Paschal’s with the aid those who observed the unreconstructed spaces. Finally, an interactive platform where a viewer could directly flip across years and view information on the neighborhood would provide a more holistic view of the neighborhood and created models.

|