The Digital Mulberry Row Project: Jefferson's enslaved alley

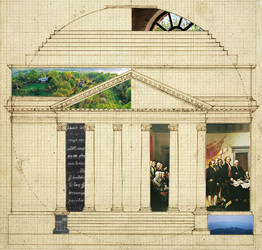

Thomas Jefferson’s legacy as a statesman, patriot, and architect of democracy was codified by his authorship of the Declaration of Independence. As a globally influential document, the Declaration contains one of the most recognized phrases in the English language, ‘all men are created equal’. However, Jefferson’s boldly penned statement did not fully invade his personal practice: he owned over 600 slaves during his lifetime and formally manumitted only seven.

Monticello, Jefferson’s home and a UNESCO World Heritage site, receives nearly half a million visitors each year. Although visitation comes from a global population, guests are universally polarized by the aspect of slavery at the home of the founding father. Some visitors are eager to question while others consciously overlook Jefferson’s life of contradiction. The architecture of Monticello further enforces this contradiction considering approximately ninety-five percent of the built fabric from the ‘big house’ dates to Jefferson’s retirement period while the architecture of the enslaved community is practically invisible. At one point in time, there were more than seventeen buildings lining Mulberry Row, a 1,000ft long swath of land that fueled the agricultural, industrial, and domestic operations of Jefferson’s plantation. Mulberry Row was the lifeblood of the mountaintop and although few physical ruins mark the land, the absence of such ruins tells a powerful story of social constructions, preservation, and memory.

This research was sponsored by a 2009 Interpretive Fellowship from the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. A longer article on the project can be found at the online journal of the University of Virginia's School of Architecture: Lunch, volume 5.

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation is conducting ongoing research on Mulberry Row; updates and highlights can be found on their website Landscape of Slavery.

Monticello, Jefferson’s home and a UNESCO World Heritage site, receives nearly half a million visitors each year. Although visitation comes from a global population, guests are universally polarized by the aspect of slavery at the home of the founding father. Some visitors are eager to question while others consciously overlook Jefferson’s life of contradiction. The architecture of Monticello further enforces this contradiction considering approximately ninety-five percent of the built fabric from the ‘big house’ dates to Jefferson’s retirement period while the architecture of the enslaved community is practically invisible. At one point in time, there were more than seventeen buildings lining Mulberry Row, a 1,000ft long swath of land that fueled the agricultural, industrial, and domestic operations of Jefferson’s plantation. Mulberry Row was the lifeblood of the mountaintop and although few physical ruins mark the land, the absence of such ruins tells a powerful story of social constructions, preservation, and memory.

This research was sponsored by a 2009 Interpretive Fellowship from the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. A longer article on the project can be found at the online journal of the University of Virginia's School of Architecture: Lunch, volume 5.

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation is conducting ongoing research on Mulberry Row; updates and highlights can be found on their website Landscape of Slavery.

Visualizing History

|

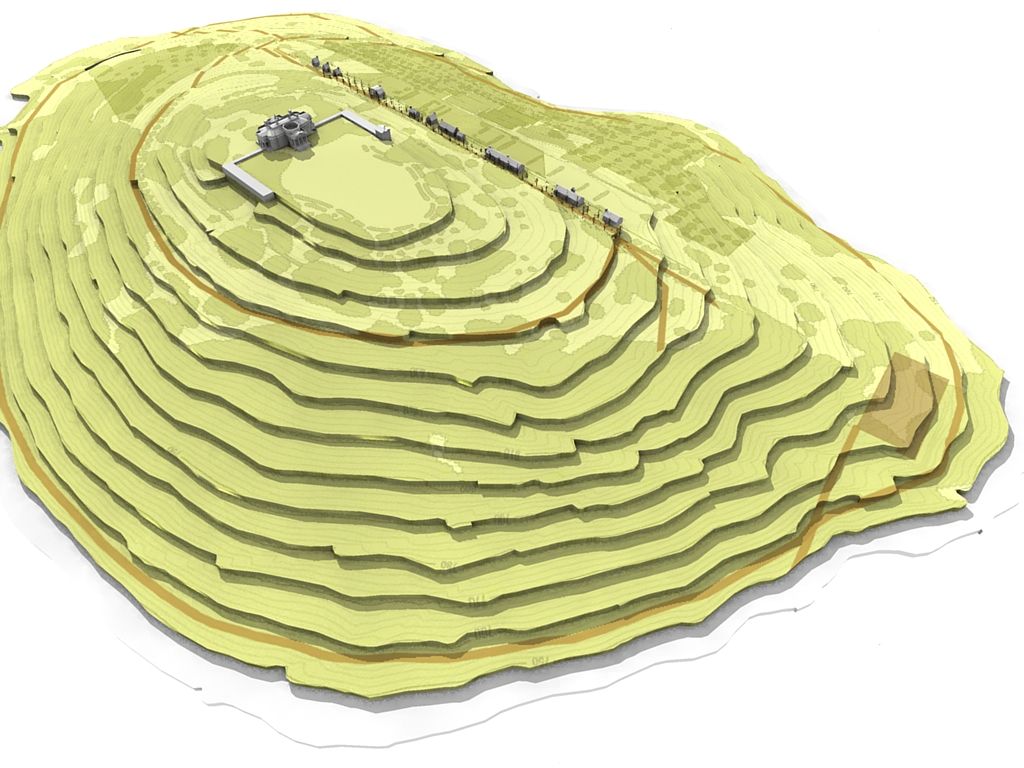

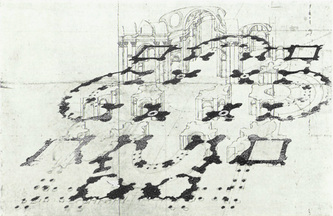

Using archaeological data and documentary evidence from the accounts of visitors to Monticello as well as Jefferson’s own letters and memorandum books, a series of digital models were created to show the spatial and programmatic evolution of Mulberry Row over three concentrated time periods: 1770-1790s, 1790s-1808, and 1809-1833. The digital models focus on the placement of the Mulberry Row structures within the landscape but do not render the materiality of these structures since more archaeological and regional architectural precedent research needs to be conducted.

Below are a series of videos depicting placement of structures along Mulberry Row as well as the specific construction elements of two types of dwelling for slaves used on the Row. Since this research project was funded as an initial investigation into the animation of documentary and archaeological evidence, different graphic styles were used in each video to illustrate the various rendering options available. |

Mulberry Row, circa 1808 |

Family dwelling, circa 1790s |