Designing a Dwelling

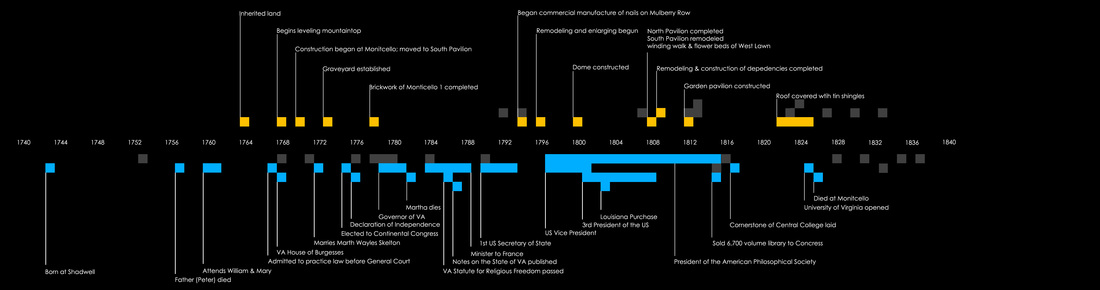

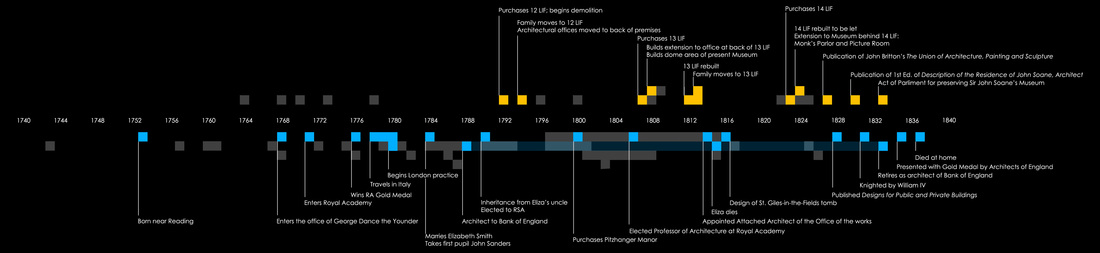

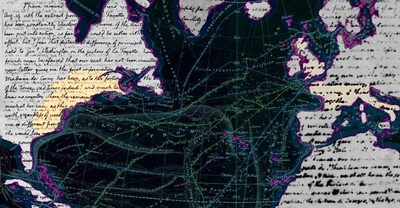

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837) developed their careers and collections on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean yet their lives shared remarkable parallels and interpersonal connections. Both gentlemen lost their fathers at a young age and quickly became dedicated, introspective students. King George III largely initiated the career of each gentleman: Jefferson’s patriotic prose in the Declaration of Independence launched his forty-year long career as statesman and Soane was granted a transformative travel grant under the sponsorship of the Royal Academy. Both gentlemen were adamantly nationalistic but also delighted in travels beyond their respective countries and shared a love of Paris. The architecture of ancient Rome inspired the work of both men. Jefferson, unlike Soane, was never able to experience the ruins for himself but the mutual admiration of sites such as the Pantheon is unmistakable. Jefferson lacked the formal education of an architect and the facility of draftsmanship that Soane enjoyed; yet both pursued a variety of architectural projects that spanned scales and programs. Professors of classicism but prophets of design deviations, Jefferson and Soane embraced new technology, methodology, and sectional qualities in their architectural work. Unfortunately, many of their projects have been lost or altered over time beyond recognition. Neither gentleman was truly credited with the enormity of his respective architectural legacy until scholarship of the early twentieth century.

A life-long love of learning fueled their bibliomania and eventually resulted in personal libraries that each contained thousands of volumes. Jefferson and Soane enjoyed the solitude and focus private study yet both actively engaged in the education of the masses. They were literal nation-builders, hoping to inspire and elevate the taste of their countrymen through built projects and collections. Jefferson and Soane were mentors to other designers within their respective nations, engaged in discourse and the design of university curriculum and held high aspirations for the future generation as evidenced through letters and their steadfast dedication to edification.

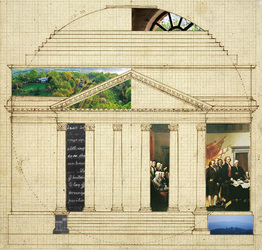

Jefferson and Soane each tackled the difficult task of designing their own ‘essays in architecture’, or personal residences. These two gentlemen became wedded to their intricate house-museums after they lost their wives. Monticello and Soane’s residence at Lincoln’s Inn Fields were both designed over the span of more than forty years. The homes were experiments in the manipulation of light, intricacies of carved space and served as vessels for the abundance of diverse collections. Drawings, models, mirrors, curiosities and gadgets adorned every open fragment of wall space and spilled from marble tables and cases. Their experimentations in residential architecture blurred the line of the public and private by providing dedicated spaces for solitary study and contemplation while also engaging the Enlightenment principle of dissemination through the program of a museum. Today thousands of visitors still enjoy the pleasure of experiencing Jefferson’s Monticello and Sir John Soane’s Museum: they are organic edifices that seem to have a life of their own beyond the assembly of brick and plaster. Although both gentlemen left behind a copious paper trail, most of Jefferson’s in written form and Soane’s through drawings, the homes and contained collections of these two men illuminate their personalities, ambitions, insecurities and legacies better than any singular record of pen on paper.

This research was sponsored by the 2007 American Architectural Foundation and Sir John Soane's Museum Traveling Fellowship. The work associated with this fellowship has formed part of the foundation for my ongoing exploration into the Transatlantic Design Network, 1768-1838.

A life-long love of learning fueled their bibliomania and eventually resulted in personal libraries that each contained thousands of volumes. Jefferson and Soane enjoyed the solitude and focus private study yet both actively engaged in the education of the masses. They were literal nation-builders, hoping to inspire and elevate the taste of their countrymen through built projects and collections. Jefferson and Soane were mentors to other designers within their respective nations, engaged in discourse and the design of university curriculum and held high aspirations for the future generation as evidenced through letters and their steadfast dedication to edification.

Jefferson and Soane each tackled the difficult task of designing their own ‘essays in architecture’, or personal residences. These two gentlemen became wedded to their intricate house-museums after they lost their wives. Monticello and Soane’s residence at Lincoln’s Inn Fields were both designed over the span of more than forty years. The homes were experiments in the manipulation of light, intricacies of carved space and served as vessels for the abundance of diverse collections. Drawings, models, mirrors, curiosities and gadgets adorned every open fragment of wall space and spilled from marble tables and cases. Their experimentations in residential architecture blurred the line of the public and private by providing dedicated spaces for solitary study and contemplation while also engaging the Enlightenment principle of dissemination through the program of a museum. Today thousands of visitors still enjoy the pleasure of experiencing Jefferson’s Monticello and Sir John Soane’s Museum: they are organic edifices that seem to have a life of their own beyond the assembly of brick and plaster. Although both gentlemen left behind a copious paper trail, most of Jefferson’s in written form and Soane’s through drawings, the homes and contained collections of these two men illuminate their personalities, ambitions, insecurities and legacies better than any singular record of pen on paper.

This research was sponsored by the 2007 American Architectural Foundation and Sir John Soane's Museum Traveling Fellowship. The work associated with this fellowship has formed part of the foundation for my ongoing exploration into the Transatlantic Design Network, 1768-1838.

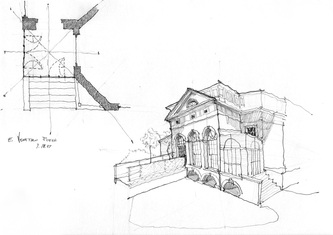

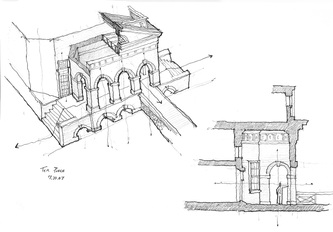

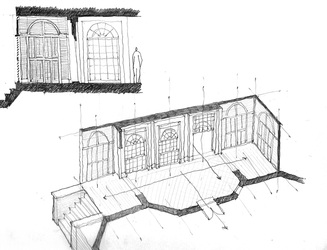

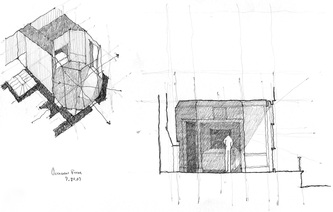

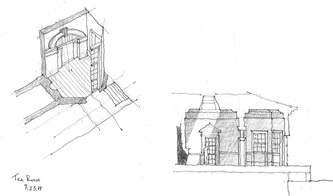

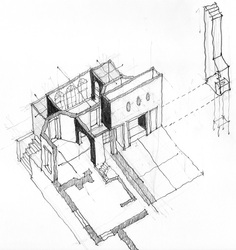

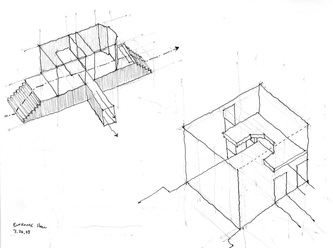

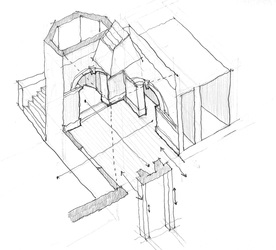

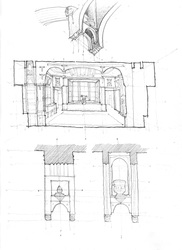

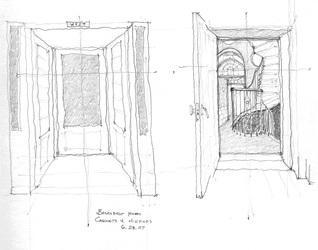

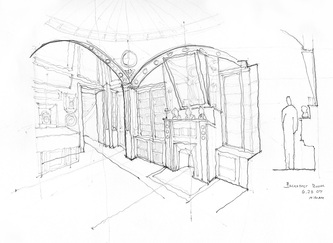

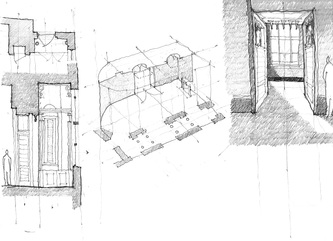

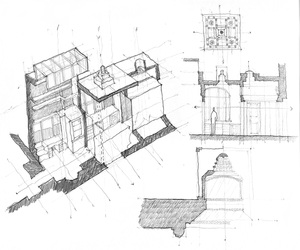

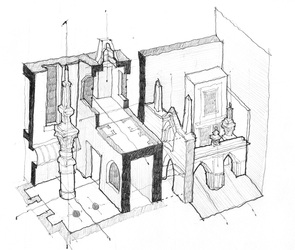

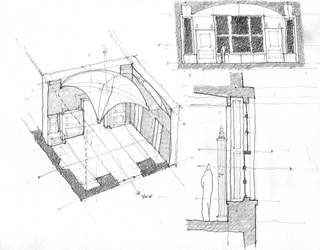

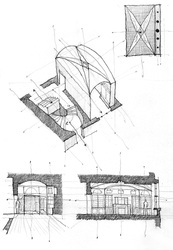

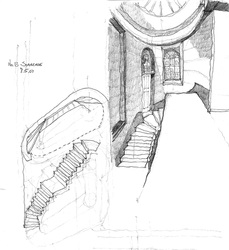

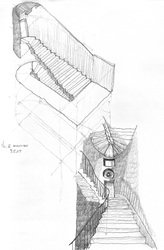

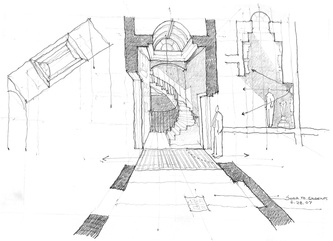

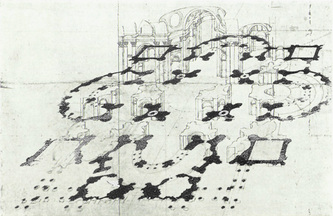

On-site Drawing

Sketching was the first part of my process into the investigation of Jefferson and Soane as architects of their own homes. By drawing portions of each home before beginning my in-depth research, I was able to formulate my own perspective on the spaces. After spending time drawing at both Monticello and Sir John Soane’s Museum I believe that the two homes can be understood as inverses from a sketching perspective. Soane’s home is understood from the inside-out: the layering starts with the space of a room covered in collections, then structured through enclosure and framed from the exterior conditions of the city. The experience of the house-museum is not closely tied to the city site. Once the front door is closed you have stepped inside another world; even the shutters of the Library’s south windows have mirrors to deflect the view back into the realm of the home. Skylights and domes are covered with wrought iron and colored glass to distort even the view of the sky. Conversely, at Monticello, every view and skylight connects the viewer to the mountaintop site. The home is understood from the outside-in: the red bricks constantly remind one that the red clay of site literally helped create the house. While seated in the Parlor looking west through the large double doors, a small, linear swath of grass obscures the stairs of the West Portico and provides an architecturally unobstructed view to the second nature of the West Lawn. At Monticello, the powerful visual connection to nature often overrules the fascination with the architecture of the interior.

Below are a series of sketches that were produced at each site. None of the drawings have been digitally manipulated or enhanced.

Below are a series of sketches that were produced at each site. None of the drawings have been digitally manipulated or enhanced.