English Avenue Elementary School

|

Investigations sposored by a 2021 NCPTT Grant

|

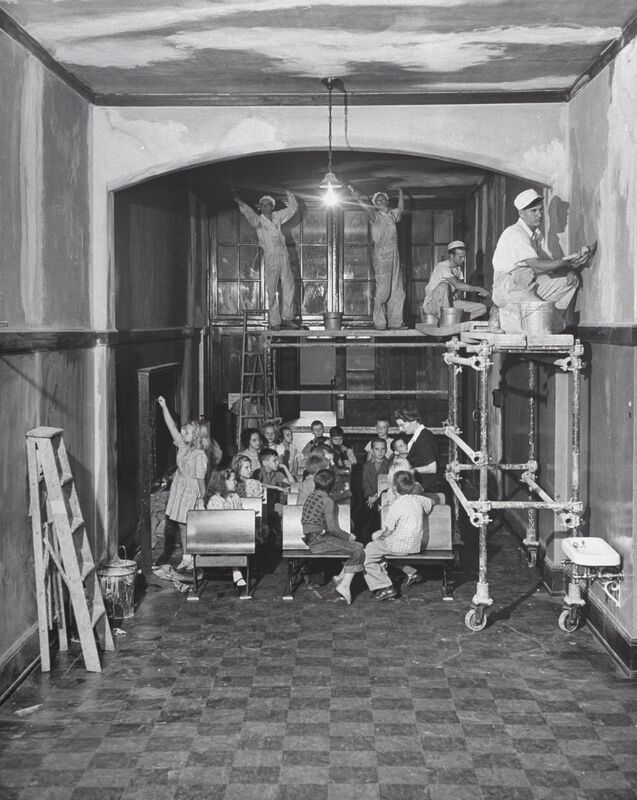

The English Tudor Revival structure of the English Avenue Elementary School (b.1911) is one of the oldest public schools in the city of Atlanta, Georgia and it was listed on the National Register in March 2020. It was originally designed for the white residents of the working-class Western Heights neighbourhood, but shifting demographics changed the designation to a ‘Black school’ in 1950. Following Brown vs. Board of Education 347 U.S. 483 (1954), an early morning bombing at the site in December 1960 demonstrated the ongoing white supremacist presence within the city, eager to express their disapproval of desegregation. The history of the site challenges Atlanta’s myth of smooth racial progress in the “city too busy to hate,” as coined by Mayor Ivan Van Allen in the 1960s. As interpretive immersion technologies advance through digital archives, collections, and databases, so do options for layered, interactive models that can advance the potential of heritage BIM (building information modelling). Incorporating these innovative interpretative methodologies for documentation and public outreach, this project explores the alignment of data collection and analysis using archival, Historic American Buildings Survey, and digital documentation methods at the English Avenue Elementary School. At the present time, the site is abandoned and structurally compromised, but plans are underway for the emergency stabilization, restoration, and adaptive use of the structure. Throughout its history, this large elementary school has been a community centre to uplift its residents. It has witnessed many moments and movements in history including women’s suffrage, child labour laws, and the pursuit of racial justice. The building is poised to be preserved, and eventually rehabilitated, but the neighbourhood is also poised for gentrification with the immerging presence of two major tech companies and the construction of the Atlanta BeltLine.

|

Site History

Historic Visualization

|

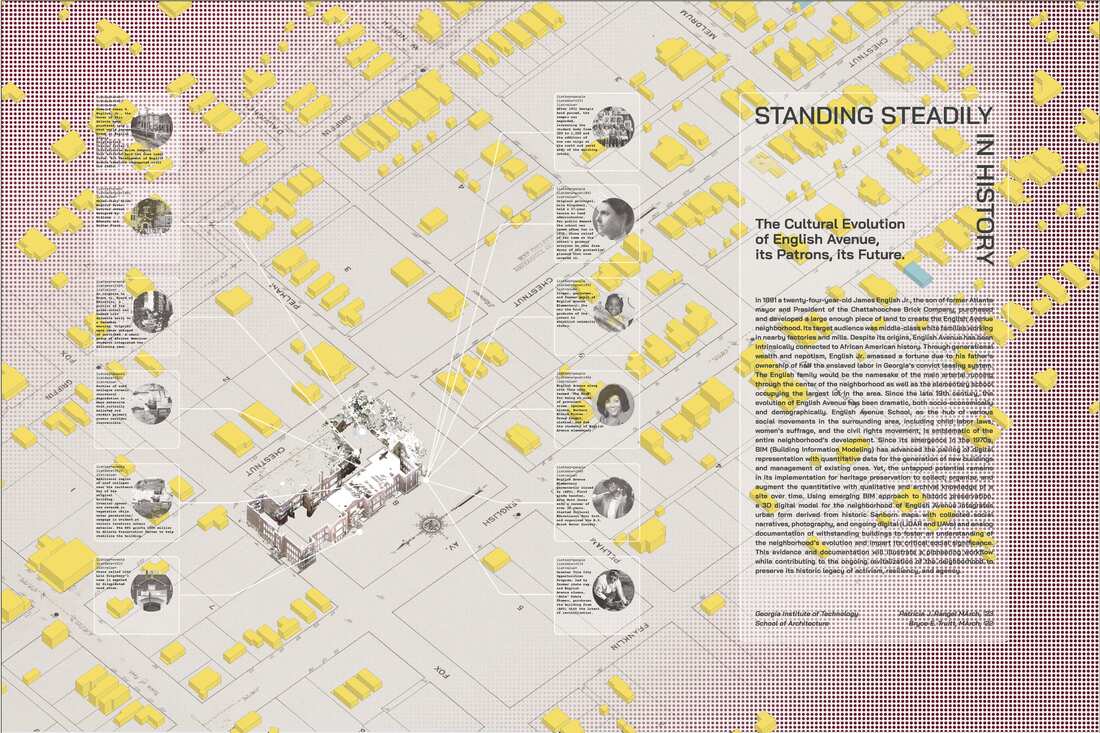

A component of this research project was to explore how Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps could be better leveraged for visualizing the historic context of sites, notated as a 'Sanborn to BIM workflow.' A 14-point guide is available here, using Rhino and Grasshopper.

|

Condition Assessment

Visualization of brick displacement on the main (west) facade.

Visualization of brick displacement on the main (west) facade.

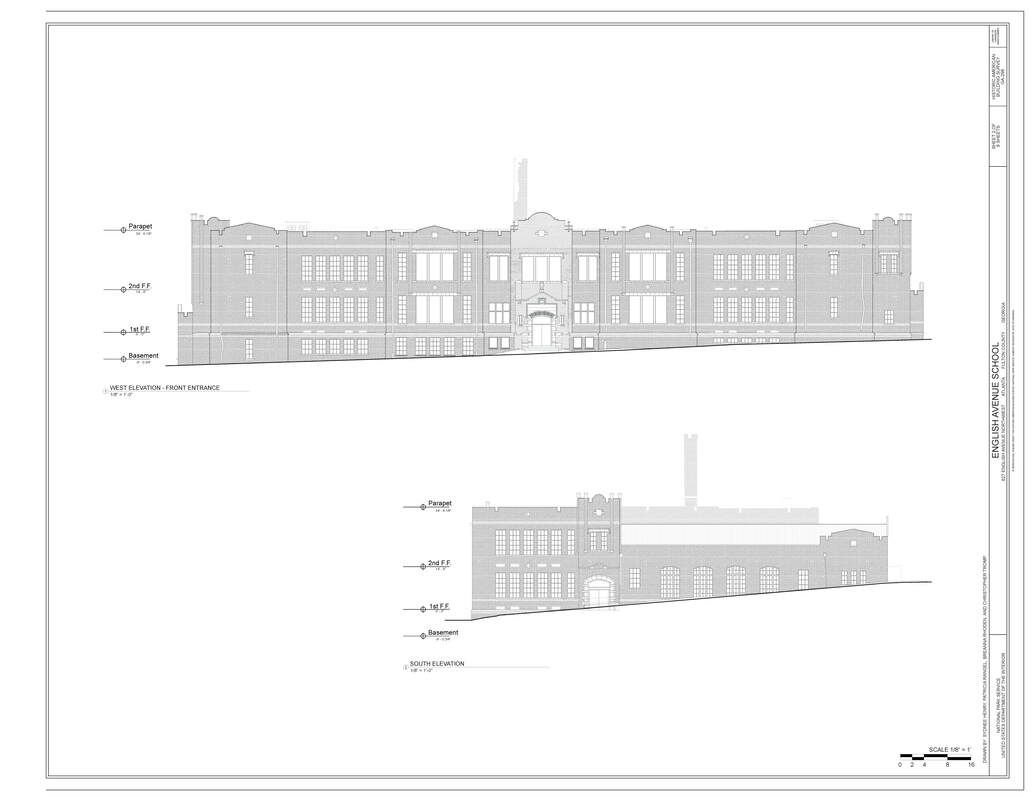

The school is significant under National Register Criterion C in the area of architecture as an excellent example of the urban public school, a significant school type in Georgia as defined by the statewide context Public Elementary and Secondary Schools in Georgia, 1868-1971. It is a representative example of this type, constructed from load-bearing brick in a then-popular revival style (English Tudor Revival), and exhibiting the type’s character-defining features, including two levels and a basement, double-loaded corridors, and vertical stair halls. Its 1923 north and south wing additions resulted in a characteristic U-shaped plan, and carried on the design elements of the original rectangular 1911 building. Both the 1911 building as well as its 1923 expansion had entrances on all sides. The original main entrance facing west onto English Avenue is intact. The school yard was open, but shade trees (now mature) were planted around three sides of the building. The architects for the 1911 building, William A. Edwards and Frank C. Walter, designed public schools across Georgia, as well as other public buildings including churches and courthouses in the region. The architects for the 1923 north and south wing additions, Sydney S. Daniell and Russell L. Beutell, designed public buildings and private residences throughout Georgia. The supervising architect for the 1923 additions, Anthony Ten Eyck Brown, also oversaw all of the 1922-23 new school buildings and additions for the APS system. A prominent Atlanta and regional architect, Brown designed houses, residences, commercial and public buildings, as well as public schools across the south.

The original owner was Atlanta Public Schools (1910-2010), then Greater Vine City Opportunities Program Inc (2010-2017), followed by Westside Development Partners, LLC (2017-Present). Original use was as a public school for white children exclusively in the City of Atlanta from 1911-1950. Then it was a public school for African American children exclusively in the City of Atlanta from 1950-1961. After Atlanta Public Schools were racially integrated, the English Avenue School remained a majority Black school from 1961-1995, when it closed its doors. Since then, the building has been abandoned and it is now its interior and portions of the exterior are substantially dilapidated, with roof collapses in several areas. The wooden windows need extensive replacement but 90% of the steel windows can be repaired. Interior damage is extensive, with 50-100% of the plaster damaged. Other repairs include drying and sealing of the foundations, major structural work, major exterior masonry repairs, removal of asbestos tile flooring, removal of unsalvageable wooden flooring while repairing the terrazzo and slab floors, repair of salvageable doors and millwork then reconstructing missing elements, and repair of concrete stairs. These preservation and restoration initiatives will allow the building to move forward with rehabilitation.

However, before any of the actions can take place, there are several steps needed to address the immediate threats to the building. In order to preserve and stabilize the building, it must first be protected. When Greater Vine City Opportunities Program (GVCOP) acquired the property in 2010, efforts were made to secure the building more completely. This has proved to be an ongoing challenge, especially as the building continues to deteriorate. Between 2014 and 2018, increasingly more interior spaces are unsafe, and more rooms have been closed off completely. However, since 2014, sections of the razor wire-topped chain link fence have been removed, making the building more accessible. Some of the plywood covering windows on the ground floor have been painted. In 2017, GVCOP installed on the grounds of the school trash containers, recycling bins, benches, a gazebo and an arbor, a stage area, picnic tables, steps to the wooded area, planter boxes, and a gravel path, in hopes of making designated areas for the community to use the outdoor spaces associated with the property that occupies two blocks, combined in the neighborhood. However, these have not been maintained. A 2022 African American Civil Rights Grant (AACRG) for the Atlanta Preservation Center (APC) sponsored safety measures to protect both the building and workers: fencing reinstalled around the entire perimeter of the building and the emergency reincorporation of much-needed aperture covers to protect the building from intrusion as well as safeguard original materials such as the 1911 wooden windows and 1923 steel windows.

Since the building closed in 1995, portions of its roof collapsed, and water infiltration produced tropical gardens in its interior. The first owners, not anticipating these long permit acquisitions, did not install temporary roofing structures to mitigate water infiltration. Much of the interior 1911 original structure has collapsed under the damaged roof. A 2020 conditions assessment report calculated a planar change of 1.25 inches on the west wall, but by July 2021, a study by Georgia Tech documented that the deflection had increased to two inches in the western façade's entry pavilion, up to four inches in the upper wall, and six inches in the bay’s walls. The building’s facades are deflecting with an increased rate of decay, so this is truly emergency work to preserve this incredible building and its story, ensuring that it can become a reborn resource for the community. Emergency brick stabilization will prevent future movement and assess substantial structure threats from the damage already done. Emergency weatherizing will prevent future rain infiltration and absorption from failed portions of the roof and non-functioning gutters and scuppers. Proposed work by Lord Aeck Sargent (LAS) will focus on the large roof membrane connecting the 1911 and 1923 sections of the main building, but the 1923 auditorium and overall drainage will need to be addressed in the interim, giving the brick time to dry. Algae and other biological growth, as well as graffiti will also have to be removed from the historic brick.

In June 2021, the Atlanta City Council passed a permit, by a vote of 13-2, to allow “the restoration and redevelopment of one of the oldest school buildings in Atlanta.” With the emergency stabilization project, the building will be ready for rehabilitation, and this will help secure the structure while the necessary permits and fundings are put into place. The protection of the building’s original construction materials is critical to the structure’s role in the story of human and civil rights in America. The building, as an artifact and through its original patronage by the English family, is an important legacy of the Chattahoochee Brick Company. The site of the fabrication facility, six miles northeast of the English Avenue School, was just listed on The Georgia Trust’s 2022 Places in Peril. The site, with ownership transfered from Norfolk Southern to The Conservation Fund and, since 2022, the City of Atlanta, no longer has the built legacy of the company, but many consider this place hallowed ground since the company was notorious for its extensive use of convict leasing, where hundreds of African American inmates were forced to work in deplorable conditions without regard to their safety. The English Avenue School’s use of building materials from the Chattahoochee Brick Company is one more connection to African American Civil Rights and as one of the largest, most architecturally decorative structures near the former fabrication site, it is perfectly poised to help tell the story.

The neighborhood is poised for gentrification with the immerging presence of two major tech companies and the Atlanta BeltLine construction on the westside. A quick intervention is necessary to salvage a structure that hangs on a thread, but also holds tremendous legacy, memory, and hope. English Avenue School is a monument literally built off the sweat, strength, and sacrifice of the community’s ancestors.

The school is significant under National Register Criterion C in the area of architecture as an excellent example of the urban public school, a significant school type in Georgia as defined by the statewide context Public Elementary and Secondary Schools in Georgia, 1868-1971. It is a representative example of this type, constructed from load-bearing brick in a then-popular revival style (English Tudor Revival), and exhibiting the type’s character-defining features, including two levels and a basement, double-loaded corridors, and vertical stair halls. Its 1923 north and south wing additions resulted in a characteristic U-shaped plan, and carried on the design elements of the original rectangular 1911 building. Both the 1911 building as well as its 1923 expansion had entrances on all sides. The original main entrance facing west onto English Avenue is intact. The school yard was open, but shade trees (now mature) were planted around three sides of the building. The architects for the 1911 building, William A. Edwards and Frank C. Walter, designed public schools across Georgia, as well as other public buildings including churches and courthouses in the region. The architects for the 1923 north and south wing additions, Sydney S. Daniell and Russell L. Beutell, designed public buildings and private residences throughout Georgia. The supervising architect for the 1923 additions, Anthony Ten Eyck Brown, also oversaw all of the 1922-23 new school buildings and additions for the APS system. A prominent Atlanta and regional architect, Brown designed houses, residences, commercial and public buildings, as well as public schools across the south.

The original owner was Atlanta Public Schools (1910-2010), then Greater Vine City Opportunities Program Inc (2010-2017), followed by Westside Development Partners, LLC (2017-Present). Original use was as a public school for white children exclusively in the City of Atlanta from 1911-1950. Then it was a public school for African American children exclusively in the City of Atlanta from 1950-1961. After Atlanta Public Schools were racially integrated, the English Avenue School remained a majority Black school from 1961-1995, when it closed its doors. Since then, the building has been abandoned and it is now its interior and portions of the exterior are substantially dilapidated, with roof collapses in several areas. The wooden windows need extensive replacement but 90% of the steel windows can be repaired. Interior damage is extensive, with 50-100% of the plaster damaged. Other repairs include drying and sealing of the foundations, major structural work, major exterior masonry repairs, removal of asbestos tile flooring, removal of unsalvageable wooden flooring while repairing the terrazzo and slab floors, repair of salvageable doors and millwork then reconstructing missing elements, and repair of concrete stairs. These preservation and restoration initiatives will allow the building to move forward with rehabilitation.

However, before any of the actions can take place, there are several steps needed to address the immediate threats to the building. In order to preserve and stabilize the building, it must first be protected. When Greater Vine City Opportunities Program (GVCOP) acquired the property in 2010, efforts were made to secure the building more completely. This has proved to be an ongoing challenge, especially as the building continues to deteriorate. Between 2014 and 2018, increasingly more interior spaces are unsafe, and more rooms have been closed off completely. However, since 2014, sections of the razor wire-topped chain link fence have been removed, making the building more accessible. Some of the plywood covering windows on the ground floor have been painted. In 2017, GVCOP installed on the grounds of the school trash containers, recycling bins, benches, a gazebo and an arbor, a stage area, picnic tables, steps to the wooded area, planter boxes, and a gravel path, in hopes of making designated areas for the community to use the outdoor spaces associated with the property that occupies two blocks, combined in the neighborhood. However, these have not been maintained. A 2022 African American Civil Rights Grant (AACRG) for the Atlanta Preservation Center (APC) sponsored safety measures to protect both the building and workers: fencing reinstalled around the entire perimeter of the building and the emergency reincorporation of much-needed aperture covers to protect the building from intrusion as well as safeguard original materials such as the 1911 wooden windows and 1923 steel windows.

Since the building closed in 1995, portions of its roof collapsed, and water infiltration produced tropical gardens in its interior. The first owners, not anticipating these long permit acquisitions, did not install temporary roofing structures to mitigate water infiltration. Much of the interior 1911 original structure has collapsed under the damaged roof. A 2020 conditions assessment report calculated a planar change of 1.25 inches on the west wall, but by July 2021, a study by Georgia Tech documented that the deflection had increased to two inches in the western façade's entry pavilion, up to four inches in the upper wall, and six inches in the bay’s walls. The building’s facades are deflecting with an increased rate of decay, so this is truly emergency work to preserve this incredible building and its story, ensuring that it can become a reborn resource for the community. Emergency brick stabilization will prevent future movement and assess substantial structure threats from the damage already done. Emergency weatherizing will prevent future rain infiltration and absorption from failed portions of the roof and non-functioning gutters and scuppers. Proposed work by Lord Aeck Sargent (LAS) will focus on the large roof membrane connecting the 1911 and 1923 sections of the main building, but the 1923 auditorium and overall drainage will need to be addressed in the interim, giving the brick time to dry. Algae and other biological growth, as well as graffiti will also have to be removed from the historic brick.

In June 2021, the Atlanta City Council passed a permit, by a vote of 13-2, to allow “the restoration and redevelopment of one of the oldest school buildings in Atlanta.” With the emergency stabilization project, the building will be ready for rehabilitation, and this will help secure the structure while the necessary permits and fundings are put into place. The protection of the building’s original construction materials is critical to the structure’s role in the story of human and civil rights in America. The building, as an artifact and through its original patronage by the English family, is an important legacy of the Chattahoochee Brick Company. The site of the fabrication facility, six miles northeast of the English Avenue School, was just listed on The Georgia Trust’s 2022 Places in Peril. The site, with ownership transfered from Norfolk Southern to The Conservation Fund and, since 2022, the City of Atlanta, no longer has the built legacy of the company, but many consider this place hallowed ground since the company was notorious for its extensive use of convict leasing, where hundreds of African American inmates were forced to work in deplorable conditions without regard to their safety. The English Avenue School’s use of building materials from the Chattahoochee Brick Company is one more connection to African American Civil Rights and as one of the largest, most architecturally decorative structures near the former fabrication site, it is perfectly poised to help tell the story.

The neighborhood is poised for gentrification with the immerging presence of two major tech companies and the Atlanta BeltLine construction on the westside. A quick intervention is necessary to salvage a structure that hangs on a thread, but also holds tremendous legacy, memory, and hope. English Avenue School is a monument literally built off the sweat, strength, and sacrifice of the community’s ancestors.

|

As part of the documentaiton of the site, four students completed a HABS submission (GA-298) for the property in summer 2021: Sydnee Henry, Patricia Rangel, Breanna Rhoden, and Chris Tromp.

|

|

|

Demonstrating the feasibility of melding digital documentation of fragmented sites with archival material to enhance historic interpretation and public outreach, this project enhances and augments sequential point cloud captures for deep climatic and structural data analysis, proposes workflows for non-invasive defect monitoring, and serves as an example of community-grounded field work within the academy.

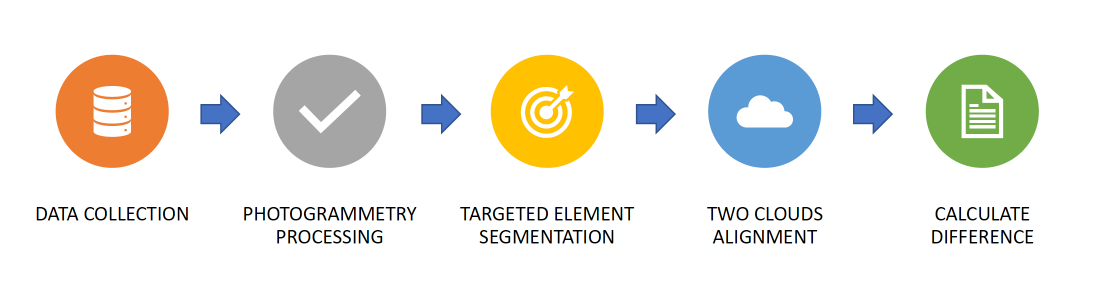

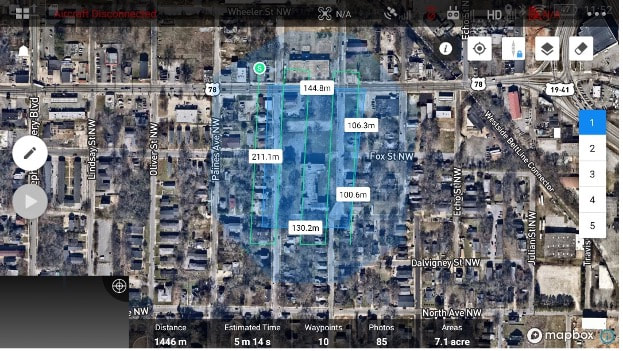

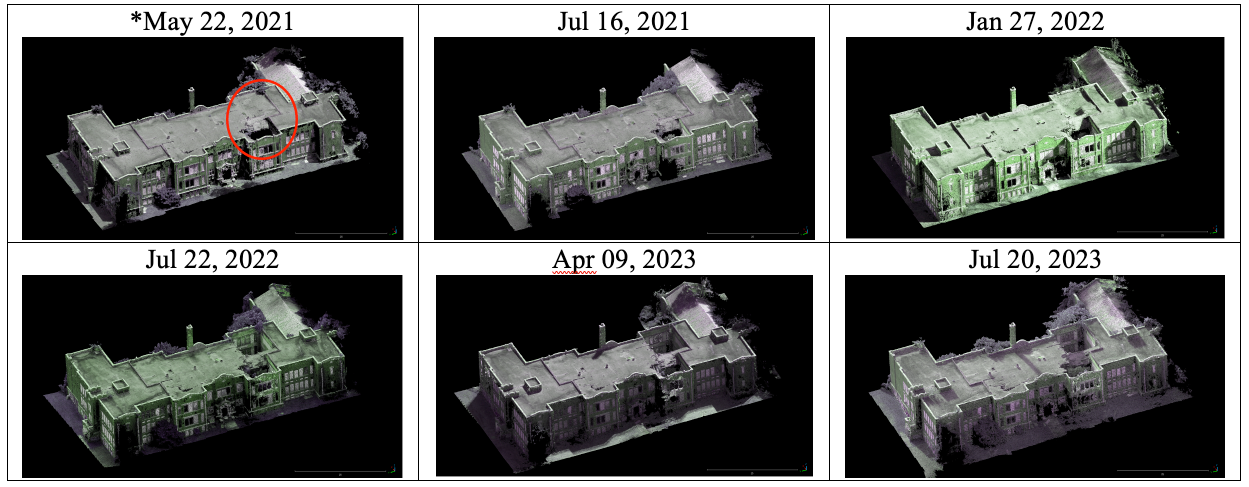

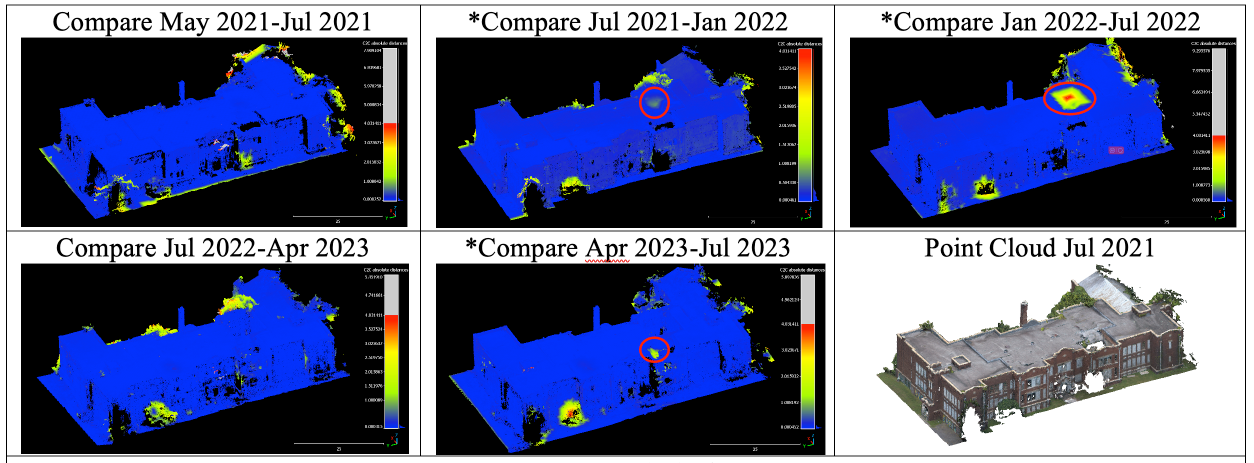

The video above explores changes to the building's structure over time, and the video to the left was captured with a DJI Avata. This non-destructive inspection technique provided a safe way to explore the upper floors of the building, compromised by structural damage. A paper, to be published through REHABEND 2024, will explore defect monitoring at the site in-depth, "Defect Monitoring and Predictive Modelling: an Atlanta Case Study." Since its emergence in the 1970s, BIM (Building Information Modeling) has advanced the pairing of digital representation with quantitative data for the generation of new buildings and management of existing ones. Yet, the untapped potential remains in its implementation for heritage preservation to collect, organize, and augment the quantitative with qualitative and archival knowledge of a site over time. Using emerging BIM approach to historic preservation, a 3D digital model for the neighborhood of English Avenue integrates urban form derived from historic Sanborn maps with collected social narratives, photography, and ongoing digital (LiDAR and UAVs) and analog documentation of withstanding buildings to foster an understanding of the neighborhood’s evolution and impart its critical social significance. This evidence and documentation will illustrate a pioneering workflow while contributing to the ongoing revitalization of the neighborhood to preserve its historic legacy of activism, resiliency, and agency. As an abandoned structure, English Avenue Elementary School has suffered from deterioration and lacking maintenance. Prior to restoration and adaptive use construction, comprehensive surveys can provide resourceful information on identifying building defects and supporting emergency stabilization. Besides, throughout long-time history and exposure to dynamic weather, historic buildings unavoidably sustain defects. Timely detection and tracking their progress become essential to ensure the safety and health of historic buildings. Meanwhile, a predictive model considering dynamic weather changes can also support the periodic building assessment before the situation worsens since historic buildings are usually delicate and hard to restore. Through a defect monitoring and predictive model, it is possible to detect latent defect progress and intervene at the early stage of inconvertible damage. Conventional building condition assessment is conducted by physical inspection, which is time-consuming and labor-intensive. In this study, Terrestrial Laser Scanner (TLS) and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV), as Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) tools, are utilized to collect building defect information. Combining TLS and drone photogrammetry technologies is deemed the most effective method for assessing and documenting heritage structures. Since most roofs and upper portions of historical buildings are hard accessible or out of range of TLS, drones are suitable devices to capture aerial information, which can compensate for TLS limitation. FromJune 2019 to July 2023, six drone captures and four LiDAR scan datasets were collected to monitor structural health by comparing those datasets from different dates. |

From visual inspection, the initial one panel of roof collapse has grown to two panels since July 22, 2022. After CloudCompare processing, more details are revealed. The same scalar field color rendering system with the same parameters is applied to all comparison results for better visual

inspection. The comparison of July 2021 and January 2022 demonstrates the early deformation of the second collapsed panel before it dropped as a whole. The result is a compelling showcase that timely emergency stabilization could be arranged when early deformation was detected on January 27, 2022, which could save much money and resources on restoration. The comparison of April 2023 and July 20223 shows last hanging roof piece of the room dropped entirely.

inspection. The comparison of July 2021 and January 2022 demonstrates the early deformation of the second collapsed panel before it dropped as a whole. The result is a compelling showcase that timely emergency stabilization could be arranged when early deformation was detected on January 27, 2022, which could save much money and resources on restoration. The comparison of April 2023 and July 20223 shows last hanging roof piece of the room dropped entirely.